December 31, 2008

Neighborhood metamorphosis (5/5)

By Lowell Brown and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe

Denton Record-Chronicle

December 31, 2008

EDITOR’S NOTE: Behind the Shale is a five-part series exploring urban gas drilling and one Argyle-area neighborhood’s struggle against it.

Opponents, backers of gas wells take up life-altering battle

Jennifer Cole stared at the letter in her hands. No matter how many times she read it, it didn’t make sense, she recalled. The letter, which appeared in her mailbox just after Thanksgiving 2007, said that a Houston company planned to conduct seismic testing so it could drill on the land behind her Argyle-area home.

Cole recalled feeling baffled. The company that was supposed to drill there, Reichmann Petroleum, was tied up in bankruptcy. Even if Reichmann had emerged from its financial hole, the city of Denton still had a pending lawsuit against the company — a lawsuit that demanded compliance with city codes before workers could move as much as an anthill. Prodded by Cole and her neighbors on Britt Drive, the city sued the would-be driller in 2006 for building a planned well site behind Cole’s home without approved plans, among other alleged violations.

But Reichmann never held the leases for that well. A Denton County lawyer, Tom McMurray, held them during Reichmann’s involvement with the site, which kept the well out of the court proceedings. McMurray pooled the leases and, on June 4, 2007, sold them to Carrizo Oil and Gas Inc., a Houston-based energy company with a multimillion-dollar budget and wells scattered throughout the Barnett Shale region.

Reading the letter, Cole said, she felt a familiar dread spread over her — the one that consumed her thoughts and stirred her prayers the day a bulldozer first moved earth behind her home. She recalled picturing the gas rig, how it would loom over her backyard — and the workers, who would see her over the fence when she was home alone. Her husband’s gas grill flashed through her mind — the grill where her boys sometimes roasted marshmallows. There it was, sitting by her backyard fence. Sometimes it sparks, she thought.

Cole and her next-door neighbor, Jana DeGrand, had led their neighborhood’s fight against the well site for two years. It was wearing on her — the hours of research and worry, days spent staring blurry-eyed at a computer screen, searching for one ordinance or state law that would stop the drilling — but Cole resolved to continue.

Not for her, but for her two boys.

“If this is where I’m called,” she said, “this is what I have to do.”

Many residents who never before felt a call to activism have been thrust to the front lines of the Barnett Shale fight. Kathy Chruscielski became concerned about her own well water when a southwestward flank of drilling rigs marched into Parker County two years ago.

After researching both hydraulic fracturing and underground injection disposal, she was asked by neighbors what she’d learned and where she’d learned it. She didn’t want the leadership role, she said, but people kept turning to her for help and she couldn’t walk away.

Fort Worth artist Don Young was willing to speak to radio, television and newspaper reporters on behalf of many neighbors who were privately alarmed when drilling rigs were set up in the city’s most pristine prairie. He pointed to long-standing problems where drilling began several years before, cautioning Tarrant County residents to look at Wise and Denton counties, likening them to canaries in the coal mine.

In Wise County, Sharon Wilson kept a diary of poor practices she saw around her home on her blog, titled Bluedaze. A Wise County neighbor who’d told her story to the Texas Observer had been threatened, so Wilson said she tried to stay anonymous. But her blog grew increasingly popular — its site meter showing that certain people inside the industry, the Texas Railroad Commission and elsewhere were logging on every day to read what she had to say. Determined, those readers who disagreed with her opinions eventually revealed her identity.

Two months ago, Chruscielski, Wilson and Young joined Dish Mayor Calvin Tillman in a site visit with several staff members of the Oil and Gas Accountability Project. The Colorado nonprofit was visiting Texas to learn more about the impact of urban drilling and, in turn, the other four were learning how to get more action out of state regulators.

OGAP had kept up public pressure until the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission rewrote rules to better protect human health and the environment — rules that were adopted in December.

OGAP executive director Gwen Lachelt said the group intends to write a manual for other communities trying to get ahead of shale development, including the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas, the Marcellus Shale in upstate New York and Pennsylvania, the Haynesville Shale in Louisiana, the Woodford Shale in Oklahoma and others.

Yet, like Franz Kafka’s protagonist in The Metamorphosis, local critics are frequently marginalized by the industry, even called names, in an attempt to starve them of their role in the broader conversation.

“We at the Powell Barnett Shale Newsletter try not to pay much attention to radical opponents of urban gas drilling,” managing editor Will Brackett wrote in July. “After all, publicity is exactly what they want and they seem to get plenty of it from the mainstream media, often to our chagrin.”

In the November 2007 issue, Gene Powell, founder of the newsletter, awarded Young his publication’s first Biggest Turkey in the Barnett Shale Award. Young says he can’t remember all the names he’s been called.

In a poignant self-description on her blog, Wilson describes how, in her journey to get the best deal for her mineral rights, she learned how her land would be used — and possibly abused. As she became more vocal, others increasingly marginalized her — until, as she writes, “without changing my core political beliefs, I became known as a radical, far-left lunatic with a political agenda.”

“If you are frustrated, angry, depressed, apathetic, horrified or just generally concerned about natural gas drilling in North Texas, mark your calendar …” Jana DeGrand read the e-mail and chuckled. It was July 30, 2008, and over the past three years she’d felt most of those emotions.

The e-mail invited DeGrand to the “Just Say Whoa!” rally in Fort Worth organized by the Coalition for a Reformed Drilling Ordinance. It came by way of Don Young.

DeGrand, whose neighborhood ordeal had consumed so much of her time, was ready to branch out.

“Don,” she replied. “I do feel that it is past time for communities across Texas to unite their efforts to reform this out of control industry. Has anyone looked into joining forces? I am willing to help.”

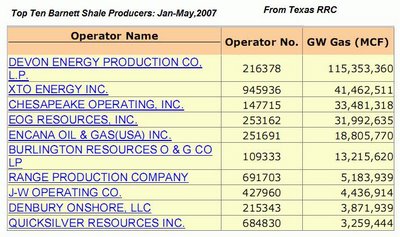

For a while, the industry appeared ready to answer some of the nagging doubts first articulated by opponents of urban drilling. Devon, Chesapeake and others formed the Barnett Shale Energy Education Council, which provides basic information on its Web site, www.bseec.org.

This year, Chesapeake Energy also published and distributed a glossy, 72-page magazine about the shale. The company rolled out an intensive campaign of television and billboard advertisements in the spring, admonishing residents to “get behind the Barnett Shale.” The campaign has since scaled back, amid news reports that actor Tommy Lee Jones was no longer participating. After hiring local news anchor Tracy Rowlett and trumpeting its planned Shale.tv, Chesapeake abruptly abandoned its plans for the Web-only broadcast, citing budget concerns. The concept lost its backing before any segment ever aired.

Although Jana DeGrand continued to follow happenings in the industry, she didn’t lose sight of her main objective: stopping the well in her neighborhood. She and Jennifer Cole continued digging, poring through deeds, contracts, anything they could use to thwart Carrizo’s bid for drilling permits. “The whole neighborhood — they’ve spoiled us,” said Cynthia Greer, another Britt Drive neighbor. “They have done so much research. So much research.”

DeGrand tried all kinds of ways to stop the drilling. In May, she’d sent a letter to four neighborhood mineral owners whose leases were expiring, urging them not to sign extensions. “Signing bonuses now range from $3,000 to more than $20,000 per acre,” she wrote. “It would be mutually beneficial to all of us if we work together.” She later explained the letter as an appeal to the recipients’ greed, in order for her to buy more time.

Later, DeGrand noticed that Carrizo’s state permit application listed the Whitespot well, named for landowners Steve and Vanessa White, as a single lease. In fact, the site was a pooled unit, comprising multiple leases, and the company had failed to submit plans showing unpooled and unleased mineral interests. The Texas Railroad Commission, which had issued a drilling permit in July, revoked it Oct. 3 after the company failed to amend its plans on time.

Later that month, DeGrand claimed in a letter to a railroad commission attorney that most of the mineral leases associated with Whitespot had expired. What’s more, she wrote, many of those who had signed might not want to renew. The man who had secured many of the leases, Jerry Pratt, was in court defending his business methods.

A one-time business partner, Robert Dunlap of Fort Worth, sued Pratt in October 2006, claiming Pratt had violated the terms of their partnership by not disclosing all of his dealings, withholding certain financial records and failing to reimburse Dunlap’s investment. Dunlap also alleged that Pratt’s many business aliases — NASA Energy Corp., NASA Energy Co., NASA Exploration Co., Command Capital Corp., Royalty Reserve Corp. — were a “sham,” saying in the lawsuit that Pratt ran all of the businesses from his Lantana home. Pratt settled the case this October, agreeing to pay Dunlap $700,000.

An attorney for Pratt, Eric C. Freeby of the Fort Worth law firm Brown Pruitt Peterson & Wambsganss P.C., declined to comment on the case. But in a letter to the railroad commission, Freeby said the lawsuit was “of no consequence” to the Whitespot permit and called DeGrand’s allegations unfounded.

Not long after sending the letter invoking Dunlap’s lawsuit, DeGrand received a letter from another of Pratt’s attorneys. Pratt would sue, the letter said, if she did not “cease and desist” all communications regarding him.

Known as a “strategic lawsuit against public participation,” a SLAPP suit is meant to intimidate, exhaust and silence critics. Widely considered an affront to the First Amendment, 26 states and one U.S. territory have adopted some kind of statutory protection against SLAPP suits. Courts in two other states also adopted such protections. Texas is not among them, as Oprah Winfrey learned after criticizing the Texas beef industry.

Although Carrizo often faces opposition to urban drilling, the Britt Drive neighbors’ level of intervention is unusual, company spokesman Michael Grimes said. Efforts to reach out to the neighbors have foundered — a reality Grimes partly blamed on the tumult preceding Carrizo’s involvement.

“Carrizo inherited the circumstances there,” he said. “In other places, we’ve been able to work through these issues.”

As officials in Austin considered Carrizo’s permit for the Whitespot well, Denton city officials worked to process the company’s application for a gas well plat, which showed the potential for four wells on the pad site. On Nov. 4, the Britt Drive neighbors made a final appeal to the City Council to deny the company’s plans.

Since they first spoke before the council in September 2006, many key officials had turned over, including the mayor, the city manager, the planning and development director and Ed Snyder, the city attorney who initiated the Reichmann lawsuit. Most critically to the neighbors, Quentin Hix had left his job as the city’s gas well inspector in April 2007 to manage the town of Copper Canyon. Denton never filled Hix’s position, choosing instead to shift his duties to the fire marshal’s office and other city departments. The change left the city without a coordinator for the departments that deal with gas drilling.

To Jennifer Cole, Hix stood alone among all the government representatives she and Jana DeGrand had appealed to. He was the one who listened, who at least tried to enforce the rules. Without him, she felt like the momentum for their cause had vanished. “It’s like starting the process over,” she said.

Despite their pleas, the city did not demand a water flow study. City planner Chuck Russell, who was handling the case, told the Coles that the law didn’t require one because the pad site was outside of a flood plain. An engineering review predicted that rainwater runoff would be “minimal” from the site because workers had added a compost berm and reserve pits.

Months before, Russell had reviewed Carrizo’s application and expressed concern about the wells’ proximity to homes. The application shows multiple houses within a 500-foot radius, including the Whites’, which is about 300 feet from the closest wellhead. But the city could not legally enforce its 500-foot setback rule in the subdivision, which is outside the city limits and only loosely falls under Denton’s jurisdiction, Russell said.

After subjecting Carrizo’s application to two rounds of review, the city approved the company’s plans Nov. 14. Now only state approval stood in Carrizo’s path.

DeGrand could only express her dismay. “Obviously,” she wrote Russell, “there is a complete lack of concern for the health and safety of our neighborhood.”

Steve White stood on the edge of a gaping pit, skipping stones across shallow water left over from the last rainstorm. The rectangular crater, which consumes the center of White’s 12-acre home site, was supposed to be gone months ago, replaced by horse stables, a barn and freshly planted trees. That was the plan, anyway, before his neighbors on Britt Drive interfered.

The pit was a temporary evil, set up to collect sludge from a gas well White thought would be drilled long before he moved his family into a custom-built home here just before Christmas 2007. Now, a year later, the well still isn’t drilled. “This has taken way longer than it should have,” he said, scanning the landscape for another stone to chuck.

To White, the neighbors’ talk of flooding is unfounded. His property is the one with a berm and detention pond. If anyone’s land is likely to flood, he said, it’s his.

His wife, Vanessa, sees her neighbors as well-meaning but misinformed. “It’s easier for them to think of us as the evil people on the hill and not get to know us for who we are,” she said. In her view, the delays in drilling only made matters worse for everyone. Each holdup allowed the dispute to fester like an open sore.

Vanessa White envisions a time when the well is drilled, the workers are gone and grass is budding where the gravelly pad once stood — a time when emotions are no longer raw and she can invite her neighbors over for a crawfish boil. In her dream, the neighbors are all friends willing to write off the past three years. “Wow,” they might say, shaking their heads, grinning, she says. “What a crummy way to get to know each other.”

Steve White isn’t so sure. He cuts off talk of a crawfish boil with a curt “Maybe.”

Gene and Jennifer Cole, mindful of the well that seemed ever more likely to drill behind them, put their home up for sale this year. People liked the house, but the pad site was a deal-breaker. They took it off the market after 30 days. “It hasn’t even drilled, and there’s still a stigma,” Jennifer Cole said. Still, the couple plans to find somewhere else to live temporarily during the drilling. They won’t have their two boys so close to it.

For the DeGrands, it’s hard to even think about moving. Everything about their home reminds them of family.

Aaron, their eldest son, died in a car wreck in January 2006. Darrin’s father, “Papa” Charlie, died nine months later.

Both were there alongside Jana and Darrin, clearing brush from their acre site when they bought it 12 years ago.

The neighbors struggle to come to terms with the thought that their efforts may be in vain. Jana DeGrand has talked about starting a Web site to share the things she’s learned, one that would save people hours of legwork and give them a sense of direction in their own battles with backyard gas wells. “But sadly,” she said, “even with that information I can’t say that it will help them.”

The ordeal has darkened Jennifer Cole’s views of the institutions she thought would protect her. She feels naive to have ever thought that she, a housewife and PTA volunteer, could beat back the gas industry, she said. Recently, a friend lamented about landowners not bothering to research their rights. “Maybe they don’t care,” Cole said, “because it doesn’t make a difference.”

At times, Cole seems resigned to the well’s arrival. After three years of prayer, of writing to her elected officials, of digging for a silver-bullet ordinance, she’s done all she knows to do.

There is no one left to appeal to.

There is nowhere else to go.

Postscript

Carrizo’s drilling permit for Whitespot remained pending Wednesday.

According to railroad commission spokeswoman Ramona Nye, the commission is asking the company to clarify which tracts are part of the pooled unit and to what extent, if any, the tracts are not leased. “Carrizo has responded to this request in part,” Nye said by e-mail.

“If Carrizo can provide some additional information required by the commission, the permit may be approved administratively, and no hearing would occur. If these issues cannot be resolved administratively, then a hearing would be required.”

LOWELL BROWN can be reached at 940-566-6882. His e-mail address is lmbrown@dentonrc.com.

PEGGY HEINKEL-WOLFE can be reached at 940-566-6881. Her e-mail address is pheinkel-wolfe@dentonrc.com.

BEHIND THE SHALE: A story of urban drilling

Chapter 1: Neighbors along Britt Drive are approached by land men eager to drill in the Barnett Shale. Some are wary of the impact on their quality of life and question whether the amount of money offered is worth it.

Chapter 2: Urban drilling means these rough-and-tumble workplaces are closer to homes than ever. But its boom-or-bust nature creates a psychosocial environment for the Britt Drive neighborhood that fosters distrust of both sides.

Chapter 3: Cities are trying to preserve their authority to make rules for health, safety and welfare, but the industry is pushing back. Britt Drive neighbors watch one such battle unfold in their backyard.

Chapter 4: A doctrine of exemption allows the industry to develop oil and gas resources without having to study the environmental or health impacts of their work. Britt Drive neighbors worry about how drilling would affect their environment.

Chapter 5: Industry insiders sometimes marginalize gas drilling opponents, but the conversation about where to draw the line in urban drilling persists. The Britt Drive neighbors’ quest to keep drillers away grows increasingly desperate.

Voicing the silence (4/5)

By Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe and Lowell Brown

Denton Record-Chronicle

December 31, 2008

EDITOR’S NOTE: Behind the Shale is a five-part series exploring urban gas drilling and one Argyle-area neighborhood’s struggle against it.

Observations, studies show subtle, long-term effects of gas drilling

For a while, Kim Couch thought her children hadn’t noticed the effect of the natural gas drilling in their neighborhood along Britt Drive.

“You think they are just in their own little world, running around and carefree,” Couch said.

Her view changed when television news cameras descended on their Argyle-area neighborhood after the first well was drilled three years ago. Couch realized that she was the one running from home to car, busy with her life and unaware of the profound changes that had come to their neighborhood. Her 10-year-old daughter, Kristen, surprised her when she answered a question about what had changed the most.

“It’s like it scared all the birds away,” Kristen said. “I can’t hear the birds sing anymore.”

Forty-six years ago, biologist Rachel Carson opened her monumental book Silent Spring with the fable of a small town ravaged by the indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides. Historians credit the best-seller with inspiring both the modern environmental movement and President John F. Kennedy, who, in response, convened a scientific commission that would become the Environmental Protection Agency.

Carson cautioned readers that her fable was not true. No single community had suffered such an aggregate of losses. However, each loss — stream banks lined with dead fish, plagues of insects bursting forth and then dying, skeletal trees and their understory silent of birdsong — had occurred somewhere in the world.

Since 2005, some residents of Britt Drive have been fighting Whitespot, a proposed gas well planned for less than 250 feet from the back door of one home on their street.

For neighbors Jennifer Cole and Jana DeGrand, the cause became a full-time job. They check in with each other almost daily, keeping track of not only developments in their own neighborhood but also developments of the urban drilling paradigm.

Each new revelation of how the oil and gas industry is regulated, as well as the short-term and long-term impacts of drilling, convinced the two women that, despite pledges by the industry to be “good neighbors,” a high-pressure gas well, condensate tanks and pipelines don’t make good neighbors.

Since Carson’s book was published in 1962, a host of federal statutes have been passed to protect the public health by ensuring clean air and water, including the Clean Air Act of 1963; the Clean Water Act of 1972; the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974; the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976; the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, known as “Superfund”; and the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act of 1986, known as the Toxics Release Inventory.

Industry lobbyists made sure oil and gas exploration and production were exempted from key provisions in all of them (I).

And prior to the Barnett Shale boom, the industry also sought and received exemptions for hydraulic fracturing — the process that pumps sand, water and chemicals to crack layers of rock, releasing the gas (II).

The oil and gas industry, which generated a total production value of $65 billion in Texas for 2007, is considered among the state’s top moneymakers, pumping funds into the economy and creating an estimated 226,000 jobs, according to the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers.

Oil and gas exploration and employment comprises about 10 percent to 12 percent of the state’s economy and is estimated to account for more than 20 percent of all state taxes.

The estimated number of drilling permits for oil and gas wells issued statewide for the year as of October 2008 is estimated at 21,330, up 26.7 percent from the same time last year.

But with the economy slowing, many drillers are idling their drilling rigs.

A Baker Hughes report this month showed 646 active rigs in Texas last week. That was down 15 from just the week before.

With the economic outlook for 2009 indicating a continued downturn nationwide, the oil and gas industry could continue to see a mixed forecast with the question of consumer demand.

The up-and-down projections could cause a slowdown — a slowdown that might provide additional time for a closer review of regulations surrounding the urban drilling paradigm.

Barnett Shale producers point to oversight by the Texas Railroad Commission as sufficient (III). Even their permit fees pay, in part, to a shared cleanup fund for operations that go belly-up.

But a crescendo of criticism — including last year’s finding by the State Auditor’s Office that the Texas Railroad Commission failed to do basic, routine inspections — suggests some troubles may be a repetitious riff of history (IV).

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Texas Legislature authorized the Texas Railroad Commission to regulate oil and gas development.

The move came with the erratic development of the oil fields around Burkburnett in the 1910s and 1920s, which had triggered colossal waste of the oil and huge economic losses.

It took years for the agency to develop a working relationship with the industry, but its weak regulatory muscles barely survived the East Texas oil boom of the 1930s.

At one point, Gov. Ross Sterling sent in the National Guard to restore order (V).

While the latest paradigm shift covers a vast, urban drilling landscape, the railroad commissioners continue to view their public mission as one of conservation — not of ecology, but of economy for the state’s oil and gas reserves.

In December 2007, an appeals court judge ruled that the railroad commission did not consider the public interest when it permitted an injection well in a Wise County neighborhood.

Since the court’s decision, the railroad commission has not written any new rules or policies to address the public interest. Instead, the railroad commission, with industry backing, petitioned the Texas Supreme Court to consider the case, which remains pending.

Before the boom, the railroad commission permitted just 75 new gas wells in 1999. More than 14,800 Barnett Shale wells have been permitted since then. In September, the commissioners, noting that the agency was buckling under the workload, redirected about $750,000 of the cleanup money to hire more people.

The money functions like a mini “Superfund,” cleaning up and plugging abandoned oil and gas wells.

Because of the commission’s weak regulatory history, previously unmapped wells are still being discovered, sometimes plugged with everything from dirt and rocks to old oil field equipment.

Those wells become underground pathways for pollution when operators are working nearby, either drilling for more oil and gas or disposing of their production waste. The migrating saltwater and hydrocarbons cause a host of environmental problems, complicating the operation of active wells around them and contaminating drinking water supplies (VI).

Perhaps the biggest potential threat of that migration comes from the underground disposal of production waste.

The Texas Railroad Commission has the largest inventory of injection wells in the nation (VII). And nearly 60 percent of the state still relies on groundwater sources for drinking water (VIII). The same process that makes groundwater safe to drink — its slow movement through rocks and sand — also makes it nearly impossible to clean once it’s contaminated (IX).

Local EPA scientists Philip Dellinger and Ray Leissner watch over the railroad commission’s regulation of more than 50,700 injection wells. Their evaluation notes each year a small but persistent level of non-compliance by some operators, as well as some catastrophic failures.

Wise County residents predicted one such failure of a proposed injection well near Chico when protesting its permit. The railroad commission allowed Hydro-FX to inject until Devon Energy reported problems at a nearby production well in early 2007. That failure followed a string of shallow injection well failures in Wise County, often reported to the agency by others.

The railroad commission has 83 inspectors, one for every 3,259 of the 270,526 active wells in the state. Although the railroad commission closed the well until Hydro-FX fixed the problem, the failure prompted an intervention by the EPA scientists concerned about drinking water supplies in Wise County (X).

Railroad commission inspectors recently closed injection wells in Parker (XI) and Wise (XII) counties after nearby residents reported failures.

In December 2007, they closed a well in Greenwood after a resident filed a complaint just weeks after another inspector gave the site a passing grade.

Railroad commission spokeswoman Ramona Nye said that operators sometimes have problems that come up after the inspection. However, after this incident, the local office decided to assign one inspector just to disposal wells, and this has increased compliance, Nye said.

Dellinger and Leissner have pressed the railroad commission to stop permitting shallow injection wells for Barnett Shale wastes, insisting that the program would be safer if drilling waste is disposed at least 8,000 feet below the surface.

“We prefer they dispose into the Ellenburger Formation,” Dellinger said. The Ellenburger, a porous limestone layer saturated with salty water, lies below the shale, locked in by the impermeable Viola Formation.

But the federal agency has not launched a full-court press for another rule change, one that would widen the area of review.

Currently, operators can calculate for quantities and pressure based on quarter-mile radius, even though a group of EPA scientists found that injected waste — once it escapes its confinement zone — has traveled up to a mile away (XIII).

U.S. public health officials have depended on the broad rules of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act to protect human health for many years, according to Dr. Roxana Witter of the Colorado School of Public Health. But the shift to urban drilling means the rules of the game have changed.

Witter and her colleagues recently published a research study and a white paper on the human health effects of oil and gas development.

Their study, which was a review of all relevant medical studies and funded by the National Resources Defense Council, found that people living in active drilling fields could be at risk for a host of adverse health effects, from reproductive and neurological problems to cancer as well as psycho-social ills.

Accustomed to dealing with human health in relation to mining in other countries, the World Health Organization advocates that regulators use health impact assessments to address risk (XIV).

This month, Colorado adopted new rules requiring the industry to consider risks to human health and wildlife before drilling in sensitive areas.

While more research is needed to assess those risks, Witter said volatile organic compounds churned into the atmosphere by the industry present risks that are well-known.

The Powder River Basin in Wyoming has a smog problem, not because of traffic, but because of intensive natural gas mining.

A new Southern Methodist University study found gas drilling and production in the Barnett Shale to be a significant source of air pollution, much greater than generated at area airports and by motor vehicles.

By 2009, residents can expect 620 tons of smog-forming compounds each day from the Barnett Shale, including 33 tons per day of toxic compounds like benzene and formaldehyde and 33,000 equivalent tons of greenhouse gases — all produced in order to mine and process clean-burning natural gas (XV).

As it bounced back from near extinction, the American bald eagle did not have nearly the public relations problem as some of Earth’s creatures have had in the political arena. Skeptics trot out the spotted owl, or the blind salamander, or the banana slug, for example, to get an easy laugh at environmentalists’ expense.

The soil, teeming with tiny life-forms, may be the least understood of Earth’s life-sustaining gifts. The soil nourishes and nurtures, particularly when fed with decaying organic matter.

But decaying inorganic materials are another matter. Radium-226 and radium-228 are the most likely radioactive daughters to stow away with natural gas and its condensate as it comes up the hole. And once allowed to contaminate the soil, they begin their deadly decay (XVI).

Jennifer Cole’s husband, Gene, with his crisp shirts, pressed pants and hair meticulously gelled and combed, fussed about the dirt in his pool from the gas pad behind his home strongly enough that the drilling company paid someone to come clean it out for him and his family.

But once the gas well is in, Gene Cole says he knows, deep down, that dirt settling at the bottom of his pool is the least of his problems.

LOWELL BROWN can be reached at 940-566-6882. His e-mail address is lmbrown@dentonrc.com.

PEGGY HEINKEL-WOLFE can be reached at 940-566-6881. Her e-mail address is pheinkel-wolfe@dentonrc.com.

FOR REFERENCE

I. “Exemption of Oil and Gas Exploration and Production Wastes from Federal Hazardous Waste Regulations,” a publication of the Environmental Protection Agency; and “Oil and Gas at Your Door? A Landowner’s Guide to Oil and Gas Development,” 2nd edition. Durango, Colo.: Oil and Gas Accountability Project, 2004.

II. “Evaluation of Impacts to Underground Sources June 2004 of Drinking Water by Hydraulic Fracturing of Coalbed Methane Reservoirs,” June 2004, EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) 816-R-04-003, www.epa.gov/OGWDW/uic/wells_coalbedmethanestudy.html.

III. Carrillo, Victor. “Riding the Shale Road,” in The Barnett Shale: The Official Magazine of Thriving on the Shale, published by Chesapeake Energy, summer 2008.

IV. Keel, John. “Inspection and Enforcement Activities in the Field Operations Section of the Railroad Commission,”Austin: State Auditor’s Office, August 2007.

V. Childs, William. “The Texas Railroad Commission: Understanding Regulation in America to the Mid-Twentieth Century,” College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

VI. “Drinking Water: Safeguards are not preventing contamination from injected oil and gas wastes,” General Accounting Office Report, July 1989.

VII. FY 2007 EPA Region 6 End-of-Year Evaluation of the Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC) Underground Injection Control (UIC) Program, Sept. 1, 2006–August 31, 2007.

VIII. Texas Water Development Board, Groundwater Resources Division, www.twdb.state.tx.us/GwRD/pages/gwrdindex.html.

IX. Ibid., “Drinking Water,” July 1989.

X. Ibid., FY 2007 EPA Region 6 End-of-Year Evaluation.

XI. Lee, Mike. “Saltwater disposal well shut down for spills, leaks,” in Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 31, 2008.

XII. Evans, Brandon. “Injection Well Shut Down,” in the Wise County Messenger, March 13, 2007.

XIII. “Does a fixed radius area of review meet the statutory mandate and regulatory requirements of being protective of USDWs (underground drinking water)?” Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Nov. 5, 2004.

XIV. Witter, Roxana, et al. “Potential Exposure-Related Human Health Effects of Oil and Gas Development: A White Paper.” Denver: Colorado School of Public Health, 2008; Witter, Roxana, et al. “Potential Exposure-Related Human Health Effects of Oil and Gas Development: A Literature Review (2003-2008).” Denver: Colorado School of Public Health, 2008

XV. Armendariz, Al. “Emissions from Natural Gas Production in the Barnett Shale Area and Opportunities for Cost-Effective Improvements: a peer-reviewed report.” Austin: The Environmental Defense Fund, 2008.

XVI. Otton, James K. et al. Effects of produced waters at oilfield production sites on the Osage Indian Reservation, northeastern Oklahoma, U.S. Geological Survey, open file report 97-28.

BEHIND THE SHALE: A story of urban drilling

Chapter 1: Neighbors along Britt Drive are approached by land men eager to drill in the Barnett Shale. Some are wary of the impact on their quality of life and question whether the amount of money offered is worth it.

Chapter 2: Urban drilling means these rough-and-tumble workplaces are closer to homes than ever. But its boom-or-bust nature creates a psychosocial environment for the Britt Drive neighborhood that fosters distrust of both sides.

Chapter 3: Cities are trying to preserve their authority to make rules for health, safety and welfare, but the industry is pushing back. Britt Drive neighbors watch one such battle unfold in their backyard.

Chapter 4: A doctrine of exemption allows the industry to develop oil and gas resources without having to study the environmental or health impacts of their work. Britt Drive neighbors worry about how drilling would affect their environment.

Chapter 5: Industry insiders sometimes marginalize gas drilling opponents, but the conversation about where to draw the line in urban drilling persists. The Britt Drive neighbors’ quest to keep drillers away grows increasingly desperate.

December 30, 2008

Culture clash (3/5)

By Lowell Brown and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe

Denton Record-Chronicle

December 30, 2008

EDITOR’S NOTE: Behind the Shale is a five-part series exploring urban gas drilling and one Argyle-area neighborhood’s struggle against it.

Texas in tug-of-war between valuable resources underground and the people who live above

Gene and Jennifer Cole stood in the backyard of their Argyle-area home, staring up at the mountain of rocks behind their fence, and then turned to a stranger in a black pickup.

“What’s the problem?” the stranger asked.

It was not a simple question. For months, the Coles and their next-door neighbors, Jana and Darrin DeGrand, had fought a gas company’s plan to dig a gas well from the dirt-and-rock plateau where the stranger stood. They had a problem with how the pad site, more than 6 feet tall, could change the flow of rainwater in their flood-sensitive neighborhood. They had a problem with the recent explosions at other North Texas rigs. They had other problems, too, but the man’s tone on that day in 2006 made them think he wasn’t interested in hearing them.

The stranger was Tom McMurray, a Denton County lawyer working with an energy company to get a rig in the ground. Because of the Coles and DeGrands, McMurray’s work had been a headache. The city of Denton cited the energy company with code violations, and the neighbors’ griping attracted media attention. When McMurray drove up, the Coles and Jana DeGrand were talking with a company engineer about how to ease their flooding concerns. The tension rose as their gaze fixed on McMurray.

“Well,” Gene Cole answered, “you’re moving so much dirt that I’m afraid that it’s going to push over into my pool.” McMurray tried talking about mineral rights with the neighbors, but the tension was so thick, he gave up.

“Welcome to Texas, Mr. Cole,” McMurray said.

For more than 100 years, the relationship between Texas landowners and the energy companies had been cordial. Even though both pay the same taxes, Texas laws have always favored the mineral interest over the surface, particularly when the property rights are severed. But the Barnett Shale’s urban drilling paradigm has wrought a Texas-sized culture clash over the rights of property owners, their neighbors and corporations.

“Where do you draw the line?” McMurray said in an interview. “That’s being debated around kitchen tables all around the Barnett Shale.”

Shari Skaggs, left, Jana DeGrand and Jennifer Cole, pictured in July 2006, helped organize their neighbors to urge the city of Denton to enforce its gas drilling rules in their neighborhood, which lies between Denton and Argyle. One proposed gas well is within 300 feet of the homes of DeGrand and Cole. (DRC file photo/Gary Payne) Shari Skaggs, left, Jana DeGrand and Jennifer Cole, pictured in July 2006, helped organize their neighbors to urge the city of Denton to enforce its gas drilling rules in their neighborhood, which lies between Denton and Argyle. One proposed gas well is within 300 feet of the homes of DeGrand and Cole. (DRC file photo/Gary Payne) |

And all around its government board rooms. For want of better regulation, cities have been drawing lots of lines, in part because the Texas Railroad Commission persists in saying it satisfies its duty to the public interest by conserving the state’s oil and gas resources.

After well explosions in Brad in 2005 and Forest Hill in 2006, some cities increased their “setback rules.” Many required somewhere between 300 and 600 feet between wells and homes or other buildings. Some city councils, otherwise poised to require longer distances, buckled as mineral owners threatened to sue for taking their property rights. But several cities upped the requirement to 1,000 feet between a well and a home or building — 250 feet more than the width of the burning crater in Brad.

As other issues emerged — crushed roads and collapsed bridges; roaring compressors and obnoxious fumes; multiple, redundant pipelines that rendered prime, developable property useless — cities sought more rules to protect the health, safety and welfare of their residents.

After workers began moving dirt behind their homes on Britt Drive between Denton and Argyle, Jana DeGrand and Jennifer Cole quickly learned that the railroad commission would offer them little help. The commission has no setback requirement (I).

City setback rules don’t apply in unincorporated areas like Briarcreek Estates, the subdivision where the two families call home. In fact, the well pad site, now known as Whitespot for landowners Steve and Vanessa White, would be illegal in both Denton and Argyle without affected landowners’ permission because the Coles’ home is within 250 feet. Outside city limits, people are generally at the drillers’ mercy — a discovery that incensed the Briarcreek neighbors.

“Our lives and our safety are not any less valuable because we don’t live in a corporate limit,” Jana DeGrand said.

State law offered one glimmer of hope. Jana DeGrand learned that cities are charged — in limited cases — with protecting the safety of residents in their “extraterritorial jurisdiction,” areas just outside city limits. After several phone calls, she and Jennifer Cole learned their neighborhood fell under Denton’s jurisdiction. Better yet, Denton’s gas well inspector agreed to investigate their concerns.

“It was like the heavens opened,” Jennifer Cole said.

Quentin Hix joined the city of Denton staff in 2002, ready to help with the city’s new gas drilling rules. As a former 13-year employee of Lone Star Gas Co., now Atmos Energy, with a degree in city management, Hix was uniquely suited for the job of gas well inspector. City rules required all drillers, even those in the extraterritorial jurisdiction, to turn in their plans for review. Some drillers skipped this step — whether out of ignorance or arrogance, Hix wasn’t sure — but he’d never seen one refuse to comply after he sent out a violation notice.

In December 2005, at Jennifer Cole’s request, Hix inspected the Whitespot well site and found violations. Reichmann Petroleum of Grapevine hadn’t filed any plans, and Hix ordered the work stopped until they were turned over and approved. By month’s end, Hix discovered the company had drilled five other gas wells, bypassing city rules for erosion control, drainage, security and well maintenance. Reichmann had also failed to get the required development permits from Denton County for the same sites. The city had no idea where pipelines were being installed, meaning anyone with a backhoe, including city utility workers, might rupture them and spark an explosion.

In a Dec. 28 letter to Reichmann, Hix threatened “further enforcement action” if the company didn’t comply.

It wasn’t Hix’s first run-in with Reichmann. In early 2005, the company took over a well north of Country Club Road. Hix inspected the site and found violations. Reichmann then started on another well before it abruptly abandoned the platting process.

As Hix learned, Reichmann had a pattern of perplexing government regulators.

Reichmann started as Richman Petroleum Corp. in 1994, a creation of Dyke R. Ferrell and F. Erik Doughty. By 2006, as the company’s fight with Denton and the Britt Drive neighbors escalated, the railroad commission had fined the company twice for state drilling violations, and had five more enforcement cases pending in various counties.

“A good operator shouldn’t have any [cases] go to enforcement,” railroad commission spokeswoman Stacie Fowler said, “because we do try to give an operator an opportunity to come into compliance with our rules.”

In 2006, as spring gave way to summer, Denton leaders faced a crossroads. Reichmann questioned their power to enforce drilling rules outside the city limits, but city leaders believed state law was on their side. Sensing an impasse, the city sued Reichmann in state district court, saying the company’s refusal to follow city rules at seven pad sites was threatening public safety. “If they’re not willing to voluntarily comply, we have no choice but to take action to force them to comply,” City Attorney Ed Snyder said of the unprecedented lawsuit.

Reichmann executives wouldn’t say much publicly, but they denied the city’s claims.

Meanwhile, Whitespot sat silent. A wood fence, roughly 8 feet tall, now separated it from Jennifer Cole’s backyard. In mid-July 2006, she told a visitor she hadn’t seen a worker there in weeks. The pressure, she said, was starting to pay off. Besides contacting the gas well inspector, she and her neighbors also sent a petition with nearly three dozen signatures to the City Council warning that failure to crack down on Reichmann’s code violations would embolden other drillers.

The neighbors scored another concession when Hix said he would require a water-flow study for Whitespot. His inspections convinced him that the dirt work had changed the runoff. Not long after the pad site went up, a 2-inch rainfall left a stream of ankle-deep water between the Cole and DeGrand homes, Jana DeGrand recalled. The volume was unusual for that amount of rain, she said.

In late September 2006, the neighbors heard that Reichmann planned to settle the lawsuit out of court. On Sept. 25, the company filed maps for most of its sites, but not for Whitespot. Company officials told the city they weren’t sure what was required. “That leaves us flapping in the wind on the one that’s the biggest issue right now,” Hix vented.

The move also left city leaders unsure of how to handle the pending lawsuit. Snyder, the city attorney, said he still wanted to send a message to other drillers to ignore the rules at their peril.

Still, the neighbors sensed that Reichmann was slowly slipping off the hook.

Since construction on the pad site started in late 2005, landowners Steve and Vanessa White had experienced their own frustrations. Steve White told a dirt mover to preserve an ancient oak tree; the man bulldozed it before his eyes, he recalled. The pad site was only supposed to cover 3 acres; workers used 4. And then there was Reichmann. The code violations embarrassed them greatly. It was sloppy, inexcusable, Vanessa White said. But a deal was a deal. “The day you sign your name to that lease is the day you don’t really have any control either,” she said.

At the same time, the Whites believed their neighbors were harassing them. More than once they said they found trash dumped into their yard. Early on, someone apparently cut through the barbed-wire fence on the north end of their land and hauled off dirt in a wheelbarrow. One neighbor kept whacking golf balls into their yard, even after Steve White asked him to stop. Others threw things at their horses, they said.

The Whites believed they hadn’t done anything wrong and sometimes resented the neighbors’ meddling. Neighbors recalled some of the alleged occurrences but doubted the Whites were the targets of concerted harassment.

Any chance to settle the feud vanished on Sept. 26, 2006, when the Britt Drive neighbors went before the Denton City Council to urge the city not to ease pressure on the newly repentant Reichmann. Waiting in their seats to address the council, some of the neighbors blithely suggested suing the Whites, who were seated nearby and overheard the remark. The neighbors later claimed they didn’t know the Whites were there, but the damage was lasting. After the meeting, several neighbors offered to sit down, to talk things out, but the Whites refused. Everyone was too agitated, they thought.

Just before Christmas, Denton city leaders discovered Reichmann had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, throwing the lawsuit into limbo. They’d have to wait until an automatic stay was removed before pressing on, the city attorney said.

Hearing the news, Jennifer Cole worried the bankruptcy would keep the neighbors from resolving their flooding concerns. “I just hope that … they are ultimately held responsible,” she said.

The following spring, the neighborhood’s fears were realized. On April 24, 2007, the heavens opened and relentless rain turned Briar Creek into a churning, rushing torrent, cutting off the neighborhood from Hickory Hill Road for hours. Uphill, the dirt-and-rock plateau for Whitespot helped push the runoff helter-skelter over Britt Drive.

When Renae Lorentz finally got home that night, after the water receded, her Suburban was gone.

Runoff washed the vehicle off her driveway and left it nose down in the creek bed, a jagged tree branch lodged through the windshield where a passenger’s head would be.

LOWELL BROWN can be reached at 940-566-6882. His e-mail address is lmbrown@dentonrc.com.

PEGGY HEINKEL-WOLFE can be reached at 940-566-6881. Her e-mail address is pheinkel-wolfe@dentonrc.com.

FOR REFERENCE

I. Despite a common perception that the Texas Railroad Commission has a 200-foot setback rule, the commission has no setback requirements. However, the misperception may come from a long-standing law in the Texas Government Code, Section 253.005(c), “A well may not be drilled in the thickly settled part of the municipality or within 200 feet of a private residence.”

BEHIND THE SHALE: A story of urban drilling

Chapter 1: Neighbors along Britt Drive are approached by land men eager to drill in the Barnett Shale. Some are wary of the impact on their quality of life and question whether the amount of money offered is worth it.

Chapter 2: Urban drilling means these rough-and-tumble workplaces are closer to homes than ever. But its boom-or-bust nature creates a psychosocial environment for the Britt Drive neighborhood that fosters distrust of both sides.

Chapter 3: Cities are trying to preserve their authority to make rules for health, safety and welfare, but the industry is pushing back. Britt Drive neighbors watch one such battle unfold in their backyard.

Chapter 4: A doctrine of exemption allows the industry to develop oil and gas resources without having to study the environmental or health impacts of their work. Britt Drive neighbors worry about how drilling would affect their environment.

Chapter 5: Industry insiders sometimes marginalize gas drilling opponents, but the conversation about where to draw the line in urban drilling persists. The Britt Drive neighbors’ quest to keep drillers away grows increasingly desperate.

December 29, 2008

Perils afoot (2/5)

By Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe and Lowell Brown

Denton Record-Chronicle

December 29, 2008

EDITOR’S NOTE: Behind the Shale is a five-part series exploring urban gas drilling and one Argyle-area neighborhood’s struggle against it.

Gas boom brings potential dangers closer to homes

Natural gas bubbled from the frostbitten ground around the well for several hours before the earth erupted about 1:45 a.m. on a December morning in 2005, tossing truck-sized boulders into the air. John Ritchie’s land erupted in a grassfire so large that a neighbor thought the sun was coming up over the scrub and cedar trees. A worker sitting in a vehicle nearby watched in horror as flames engulfed him.

Emergency workers scrambled to control the blaze near Brad, in Palo Pinto County, but soon discovered more gas leaking out of fissures in the ground on the other side of U.S. Highway 180. While the worst-case scenario never materialized — more explosions on both sides of a major thoroughfare and a much larger conflagration — the gas-fed fire burned uncontrollably for several days within a 750-foot-wide crater that ranged from 30 to 60 feet deep.

While blowouts and well control problems are uncommon, records with the Texas Railroad Commission show that they have occurred, and continue to occur, in the Barnett Shale.

Most have been in Palo Pinto County and, except for the Brad explosion, no one reported a gas blowout that also resulted in fire or injuries. Stoval Operating lost control of a well on June 18, 2002. Two other operators lost control just before the explosion in Brad. On Sept. 29, Jilpetco had drilling mud blow out and into the reserve pit.

A Devon Energy worker fell about 90 feet from the top of this drilling platform off Hamilton Drive in Argyle in February 2007. He survived with broken bones. (DRC file photo/Gary Payne) A Devon Energy worker fell about 90 feet from the top of this drilling platform off Hamilton Drive in Argyle in February 2007. He survived with broken bones. (DRC file photo/Gary Payne) |

A month later, McCown Engineering had a blowout during drilling. Palo Pinto County operators didn’t report any more problems to the commission until April 25, 2007, when Upham Oil & Gas lost control of a well while its employees were adding pipe.

Until December 2005, any problems operators had in this sparsely populated area of the Barnett Shale escaped the attention of city dwellers who still thought of natural gas drilling as a rural enterprise. Telesis Operating Co.’s loss of control in Brad injured only one worker, the man who was sitting in his vehicle at the time of the blast. He suffered only minor flash burns and returned to work that day.

The events coincided with energy companies trying to convince thousands of property owners in the Barnett Shale to sign on to their plans for urban drilling.

Jennifer Cole turned on her television and learned of the destruction in Brad, 100 miles away from her well kept home near Argyle. She gasped. The devastation confirmed her worst fears about urban drilling

For weeks, Cole and her next-door neighbor, Jana DeGrand, had been fighting a gas company’s plan to erect a rig less than 300 feet from their back doors. A bulldozer appeared in the empty lot behind them and started building a pad site, a scant few feet away from their back fences. Worried all the dirt moving would alter runoff in their flood-prone subdivision — an additional concern for the Britt Drive neighborhood — they called and wrote their elected officials but found little help. Government agencies lacked the power or the will to investigate their concerns.

Maybe the explosion in Brad would make a difference, DeGrand recalled thinking. Maybe now people would take her concerns seriously. After all, if the same explosion happened at the pad site behind her, creating the same 750-foot crater, she and her neighbors could be dead.

The effort was becoming a full-time job for DeGrand and Cole, leaving little time for leisure. Cole, a stay-at-home mom, and DeGrand, an event marketer, spent hours online and at the county courthouse, researching deeds, contracts, laws — anything that might help their cause. They also scanned the media for industry news, with each report of lax regulation, explosions or environmental harm hardening their opposition to urban drilling. They wondered if an industry that was accustomed to drilling in pastures should really be trusted in areas with no room for error.

“No one wants to live in fear that when the rig comes in, what if an explosion happens?” Cole said. “What if there is a gas leak? What if there is a blowout? It should not be put in the middle of a neighborhood where the homeowners have these issues to deal with.”

Four months after the Brad explosion, one Fort Worth neighborhood dealt with those very issues. An explosion at a Forest Hill wellhead on April 22, 2006, killed XTO employee Robert Gayan, 49, and forced nearby residents to evacuate their homes.

That incident, as with most other fires and explosions at drilling and disposal sites, tank batteries, pipelines and compression stations, was not the result of a blowout. But the problem underscored the difficult and dangerous work of prying the volatile matter from Earth’s grip and harnessing it into usable energy.

When compared with workers in other industries, oil and gas workers are hurt and killed on the job with disproportionate frequency. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2003 to 2006, the most recent data available, occupational fatalities occurred at a rate of 4 per 100,000 workers for all workers. Not only are oil and gas workers getting killed on the job at nearly eight times that rate, but the fatality rate has increased since the uptick in exploration and production nationwide: from 30.5 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2003 to 31.9 per 100,000 in 2006 (I). On July 2, 2003, employees of Felderhoff Brothers Drilling were setting up a rig west of Fort Worth when Terry Bressler, 43, was pinned between a housing section and the floor of the drilling rig. The others could only watch as he was crushed and killed (II).

On April 19, 2005, as a Patterson Drilling crew prepared to drill a new horizontal well near Decatur, Tab Stewart Dotson, 46, backed his forklift into the old well. The tire knocked off the well cap, igniting the gas into a flash fire that trapped him inside the cab. Fellow employees of Patterson Drilling extinguished the fire only to watch Dotson die (III).

On July 14, 2006, Charles Mannon, 38, died after falling 90 feet from the top of a Cheyenne Drilling Co. rig in Saginaw. As when Gayan was killed 14 months before in Forest Hill, local media reported that XTO Energy blamed the employee for the accident, claiming that the industry has strict safety procedures (IV).

In addition to a higher risk of dying on the job, oil and gas workers face risk of serious injury or illness at work. From 2003 to 2006, the nationwide incident rates for on-the-job injuries in the mining sector were worst for those involved in drilling, at a rate of 5.3 per 10,000 full-time employees. Those in well-servicing jobs face comparatively less risk, at 3.1 per 10,000, with 2 per 10,000 injured in extraction jobs. However, because of differences in reporting among different labor sectors, comparing oil and gas occupational injury and illness rates with rates in non-mining jobs is meaningless, according to a September 2008 report by the Colorado School of Public Health.

On Feb. 12, 2007, a Devon Energy employee working on a rig between Denton and Argyle fell 90 feet from the top of a drilling rig, a fall that is usually fatal. The employee, who was wearing a hard hat, managed to land on his feet on the metal platform below and survived with broken bones (V).

Argyle Fire Chief Mac Hohenberger noted that whenever paramedics are dispatched to help with injuries at a gas well site, “it’s always pretty bad.”

This physically risky work, born in a fiscally risky environment, foments a rough-and-tumble culture that frequently doesn’t play well to outsiders.

At the beginning of the boom, two employees killed a fellow worker Nov. 25, 2003, in an initiation prank at a rig near Argyle. Teddy Garland and Louis Goodman intended to string Shawn Davis up with a line used to move heavy pipe. Instead, the line became entangled in the machinery, dragging Davis headfirst through a door and slamming him around and around. The men unhooked the line from Davis’ belt, washed off the blood and concocted a story to cover their ill-fated prank. It was all a fluke, they’d told authorities; Davis entangled himself in the chain accidentally.

The next day, a co-worker went to the sheriff’s office and revealed the truth of what happened. At trial, Goodman testified that initiations and horseplay were simply part of the roughneck’s life. Davis “more or less played along with it,” Goodman testified. “He was laughing.”

A jury found Goodman guilty of manslaughter and sentenced him to 18 years behind bars. Four months later, Garland pleaded guilty to the same charge and accepted a five-year prison sentence.

The brutal episode so close to her home haunted the thoughts of Jennifer Cole. She tried not to picture the trailers and drilling equipment arriving just beyond her back fence. Trailers that would fill up with workers. Workers who would know when her husband left for work, when she was alone with her boys. She tried to bat the thoughts away, to believe that she was worrying too much. But they came anyway. What kind of people would do such a thing, she recalled wondering, replaying the details of Davis’ death in her mind. Is that what she should expect from them? These would-be neighbors?

LOWELL BROWN can be reached at 940-566-6882. His e-mail address is lmbrown@dentonrc.com.

PEGGY HEINKEL-WOLFE can be reached at 940-566-6881. Her e-mail address is pheinkel-wolfe@dentonrc.com.

FOR REFERENCE

I. Witter, Roxana, et al. “Potential Exposure-Related Human Health Effects of Oil and Gas Development: A Literature Review (2003-2008),” Denver: Colorado School of Public Health, August 2008.

II. Compiled from Tarrant County Medical Examiner and Occupational Safety and Health Administration records.

III. Compiled from court documents, Dotson vs. Encana Oil & Gas, Cause No. 06-05-357.

IV. Mosier, Jeff. “Gas firm blames worker for blast in Fort Worth,” in The Dallas Morning News, April 26, 2006.

V. Board, Jay. “Man injured in fall from rig in Argyle,” in the Argyle Messenger, Feb. 12, 2007.

RISKY WORK

A Colorado School of Public Health review found that the fatality rate among oil and gas workers was 31.9 per 100,000 workers in 2006. According to another report, differences in reporting among different labor sectors make it meaningless to compare oil and gas occupational injury rates with rates in non-mining jobs.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released a preliminary analysis of on-the-job fatalities for 2007 in October. The agency will release final numbers for 2007 in April 2009. Listed are fatality rates per 100,000 workers.

TOP 10 MOST DANGEROUS JOBS

1. Fishers and related fishing workers, 111.8

2. Logging workers, 86.4

3. Aircraft pilots and flight engineers, 66.7

4. Structural iron and steel workers, 45.5

5. Farmers and ranchers, 38.4

6. Roofers, 29.4

7. Electrical power line installers and repairers, 29.1

8. Drivers/sales workers and truck drivers, 26.2

9. Refuse and recyclable material collectors, 22.8

10. Police and sheriff’s patrol officers, 21.4

BEHIND THE SHALE: A story of urban drilling

Chapter 1: Neighbors along Britt Drive are approached by land men eager to drill in the Barnett Shale. Some are wary of the impact on their quality of life and question whether the amount of money offered is worth it.

Chapter 2: Urban drilling means these rough-and-tumble workplaces are closer to homes than ever. But its boom-or-bust nature creates a psychosocial environment for the Britt Drive neighborhood that fosters distrust of both sides.

Chapter 3: Cities are trying to preserve their authority to make rules for health, safety and welfare, but the industry is pushing back. Britt Drive neighbors watch one such battle unfold in their backyard.

Chapter 4: A doctrine of exemption allows the industry to develop oil and gas resources without having to study the environmental or health impacts of their work. Britt Drive neighbors worry about how drilling would affect their environment.

Chapter 5: Industry insiders sometimes marginalize gas drilling opponents, but the conversation about where to draw the line in urban drilling persists. The Britt Drive neighbors’ quest to keep drillers away grows increasingly desperate.

December 28, 2008

Eminent dominance (1/5)

By Lowell Brown and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe

Denton Record-Chronicle

December 28, 2008

EDITOR’S NOTE: Behind the Shale is a five-part series exploring urban gas drilling and one Argyle-area neighborhood’s struggle against it.

Expansion of natural gas industry into Barnett Shale leaves Argyle families little recourse

Jennifer Cole stepped across the parched ground of a North Texas autumn, past her dirt-caked backyard swimming pool, inching closer to a roaring machine. She watched it force its way through the earth, pushing dirt from side to side in waves like an ocean’s tide. Day by day, the bulldozer was remaking the lot behind her home on Britt Drive near Argyle, changing a sloped meadow dotted with oak trees and cattle into a flat and lifeless expanse. She shivered when she thought about what would fill the void.

Since the dirt-moving process began, dust clouds became so thick that her boys couldn’t make sense of them. “Mom, look! A sandstorm,” one said. Her sons didn’t understand why she wouldn’t let them use the pool or play outside after school. She looked down at the pool where a layer of grime clung to the bottom like black frosting, then back to the rolling bulldozer on the other side of the barbed-wire fence.

Cole didn’t know that what was happening behind that fence would consume the next three years of her life. She did know what the bulldozer meant, though. A gas rig was coming. It was Dec. 4, 2005 — a Sunday.

“Sunday,” she said above the roar, “is no day of rest.”

Jennifer Cole makes bark candy with her boys Jared, 12, left, and Gentry, 9, for a Christmas party. Cole has struggled to maintain a normal home life for her sons amid her neighborhood’s ongoing battle against a pending gas well behind their Argyle-area home. (Denton Record-Chronicle/Barron Ludlum) Jennifer Cole makes bark candy with her boys Jared, 12, left, and Gentry, 9, for a Christmas party. Cole has struggled to maintain a normal home life for her sons amid her neighborhood’s ongoing battle against a pending gas well behind their Argyle-area home. (Denton Record-Chronicle/Barron Ludlum) |

Cole and her neighbors were among many visited that year by energy land men, deal-makers slowly blanketing North Texas after one company proved a decade ago that it could release the “sweet gas” — typically 95 percent methane, with small amounts of ethane and propane — of the Barnett Shale with a sand-and-water fracture.

But the thousands of natural gas wells and miles of high-pressure pipelines unfolding into a massive industrial zone would never be aggregated by government regulators. The latest federal rules continue the practice of exempting oil and gas that began in the 1970s.

In its publications, the Environmental Protection Agency details industry exclusions from federal environmental laws that touch nearly everyone else, from the neighborhood dry cleaner and the horse rancher to the gravel yard and the truck manufacturer.

Texas agencies flex few regulatory muscles over the industry, deferring to the Texas Railroad Commission, which, a century ago, assumed responsibility to maximize oil and gas production, not address the host of concerns that have come with the new urban drilling paradigm — a paradigm where once rural drilling has shifted into the heart of neighborhoods amid cities.

Faced with the eastward march of tank batteries and pipelines, cities of the Barnett Shale began exercising powers granted to them by the Legislature. The energy companies then resisted local rules meant to protect public health and safety, land use planning and economic development by filing a spate of lawsuits in the past year.

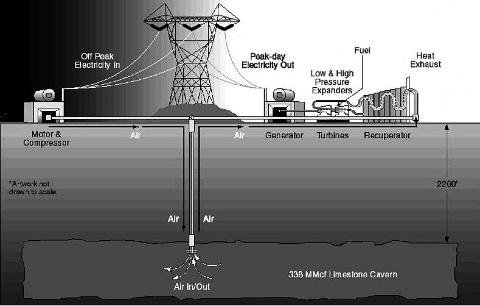

Meanwhile, the industry grabbed the biggest hammer in government’s exemption toolbox — the power of eminent domain — by forming their own utility companies. With it, they began connecting their gas wells like a giant dot-to-dot game across lawns and schoolyards.

Oil and natural gas are the decayed remains of organic matter that became trapped under layers of stone and sand long ago, said EPA scientist Philip Dellinger. In the case of the Barnett Shale, that decay took place more than 300 million years ago during the Mississippian Age, and the gas has been trapped ever since. Geologists found outcroppings of the black, organic-rich shale a century ago in San Saba County and named it after John W. Barnett, a settler there.

Some longtime residents knew of the shale’s potential in North Texas. Jana DeGrand, Cole’s next-door neighbor, remembers how her father, a tenant farmer, drilled for water, and natural gas would come up with it.

Energy speculators knew about it, too, but the tight rock held fast to its riches. As late as 1983, a Carrollton energy man resisted the urge to explore in Denton County.

“Every time I get the urge to look for gas, I just lay down until the urge passes,” Doug Durham said to a newspaper reporter then.

But another energy man, George Mitchell, believed decades ago that the shale could be broken. Energy workers speak emotionally, almost reverently, of Mitchell’s determination to unleash 26.7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (I) bubbling beneath the feet of more than 3 million North Texas residents (II).

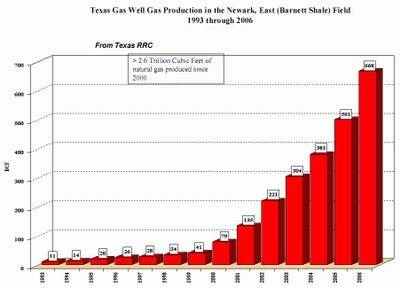

Once Mitchell’s company proved the work could be done with a solution that began with cheap, fresh water and sand, the drilling boom began. Thousands of vertical wells were dug between 1999 and 2005, primarily in Wise and western Denton counties.

Improvements in horizontal drilling followed. Operators turned their drill bits through the shale while watching a computer screen, like joy sticks on a video game, capturing gas thousands of feet from the well head and turning modest producers into multimillion-dollar holes.

With horizontal drilling under their command, the industry set its course for the more populated parts of Denton County and the mother lode of Tarrant County, where geologists believed some of the richest deposits lie. One Encana engineer, Jim Kramer, his eyes focused down the well holes as the company worked its way into Tarrant County through Keller, imagined out loud in 2006 about having the entire city of Fort Worth picked up and moved over so the company could drill.

The letters from land men in summer 2005 promised the Coles, the DeGrands and their Britt Drive neighbors a chance to cash in on the North Texas gas boom. Several rigs popped up near their Briarcreek Estates subdivision south of Denton that year — enough for some neighbors to question whether the towers of industry belonged so close by.

Earlier that year, Jana DeGrand and her husband, Darrin DeGrand, were driving home when they encountered a foot of mud on a road leading into the neighborhood. Trucks hauling dirt to a pad site on Fincher Road left a trail of debris, and heavy rains made the road nearly impassable. When the couple finally made it home, they recalled, mud clung to every inch of their car’s undercarriage.

Later, drilling at the same site rattled windows on Britt Drive a quarter-mile away. The noise continued nonstop for weeks. Darrin DeGrand recalled lying in bed at 3 a.m. many times, unable to sleep through the cacophony of mechanical grinding and squealing. His wife finally called the sheriff’s office to complain one day, remembering that a deputy once threatened to fine her daughter for playing her guitar too loudly.

“Can’t they stop between 10 and 6 so we can sleep?” she asked.

No, the answer came. It’s for the greater good.

In November 2005, a state inspector found oil-stained soil at a well site off Hickory Hill Road. Jana DeGrand, whose complaint spurred the inspection, said the stench was overpowering.

So the DeGrands were wary when a Lantana-based energy company started asking the Britt Drive neighbors to lease their mineral rights to allow more drilling in the area. The company, NASA Energy Corp., arranged an evening meeting to convince the neighbors to sign on. Huddled around a conference table inside a Denton bank, nearly a dozen neighbors peppered land man Jerry Pratt with questions.

“What happens if you damage our homes?” Darrin DeGrand asked, worried that vibrations from drilling or seismic testing would damage foundations. Where will the wellhead be? Others wanted to know.

The DeGrands believed that Pratt, who’d brought a jar of fracing sand for show and tell, initially tried to sidestep the questions. Pulling out a map, he pointed to spots where rigs might be. The DeGrands knew one of the spots instantly. It was right behind their house.

A few neighbors accepted Pratt’s offer of a $250 sign-on bonus (later increased to at least $500). But others asked to hold off until the DeGrands could research the matter.

“There’s always one crazy person in the neighborhood,” Darrin DeGrand recalled Pratt saying.

“Well,” he remembered replying, “I guess we’re it.”

Because the Energy Information Administration estimates the average well costs about $1.9 million to drill (III), land men know that acquiring the mineral rights from landowners can be the least expensive part of the deal. But media reports of payouts to landowners for signing the leases show the amounts can be highly variable. Similar to Pratt’s offer to the Britt Drive neighbors, residents of one Fort Worth neighborhood — primarily poor, black and elderly — received $200 checks to sign on the spot, in addition to a 20 percent royalty in 2006 (IV ). Two years later, residents in affluent areas of Johnson and Tarrant counties got more than 50 times that payout, with $25,000 to $30,000 per acre, averaging about $10,000 for each household simply to sign. Their agreements included royalty payments that varied from 25 percent to 25.5 percent (V).

Mineral rights run with the land in Texas, unless a previous owner retained them when selling, or has already leased them. In Dish, near the birth of the Barnett Shale boom, relationship problems between the landowner and the industry are like a family science study. Some landowners remain comfortable in their marriage to the industry as it goes into its second decade. Tiffany Pennington’s family negotiated a deal with Devon Energy that keeps them comfortable, she said, struggling to understand why others complain. Next door, Jim and Judy Caplinger bought their home on land with mineral rights already separated, leaving them without access to the underground riches. When the industry gets hungry — needing additional pipeline access or more land for another well — the couple watch as their nest egg shrivels, sometimes through eminent domain.

Their case is similar to many other families who, until recently, bought land in a Barnett Shale county not knowing that living in Texas, with its laws and rules covering mineral rights, can still pit neighbor against neighbor.

Some landowners negotiate more for the signing bonus than the royalty payout, which can last for three decades or more. One industry analysis found the average Barnett Shale homeowner would net about $775 per year for 30 years (VI). In their negotiations with landowners, energy companies went along with the splashy, upfront payouts for about a year. But after the credit meltdown this September, energy companies, including Chesapeake, Vantage, XTO and Titan, announced publicly that they would no longer be making those news-making payouts (VII).

The Briarcreek Estates subdivision, tucked into the Cross Timbers between Denton and Argyle, winds all the way along the creek that cuts through it, served only by a narrow, curving road off Hickory Hill Road that ends in a cul-de-sac. Britt Drive offers the only entrance and exit to the three dozen families who live in the neighborhood. They flocked here for the large lots — many are an acre or two — and the country feel. Hordes of birds, cardinals, finches and mockingbirds sing from the trees, and raccoons, opossums and armadillos search for food along the creek bed. Neighbors share fruits and vegetables from each other’s gardens and look after each other’s pets when they’re away. They gladly serve iced tea to guests, and strangers driving through are likely to be greeted with a wave and a nod.

Darrin and Jana DeGrand were among the first to build in the neighborhood. In 1996, the couple, with their three children and his parents, grabbed pickaxes and a lawn mower and cleared the acre lot themselves, beating back briars and underbrush. Darrin, a data technician for a telephone company, and Jana, an event marketer, designed the house on their home computer and built much of it themselves.

Gene and Jennifer Cole moved in next door to the DeGrands in 2002. Gene, a manager at a car dealership, and Jennifer, a stay-at-home mom and PTA volunteer, wanted their two young boys to grow up in the Argyle school district.

Like many of their neighbors, the Coles and DeGrands hurried to research their mineral rights once NASA Energy started dangling contracts in 2005. The DeGrands, who own adjoining lots and claim at least partial mineral ownership of one of them, refused to sign, hoping to keep any driller as far away as possible. The Coles dug out their house’s title policy, which shows they own three-fourths of the minerals on their lot, but they quickly learned that meant little.

Denton County lawyer Tom McMurray, who took over the area leases from land man Jerry Pratt, did his own title check and claimed the Coles owned no minerals. McMurray, through his CMC Exploration Co., was working with Grapevine-based Reichmann Petroleum to develop the well site behind the Cole and DeGrand homes. In a letter to the Coles in late 2005, McMurray offered a concession. The landowners decided to erect a wood fence along the property line to cut down on dust and noise and deter children from wandering into the site, he explained. “We do want to be good neighbors while also developing the assets of the mineral owners,” McMurray wrote. “Please understand that we follow the law and instruct our employees to do the same.”

Before the end of 2005, NASA Energy dropped a contract at the Coles’ door despite the disputed mineral rights. It went unsigned. Other neighbors joined the Coles and DeGrands in rejecting the land men’s offers. “We were told that it would work out to about $100 a month [in royalties] if things went really well,” neighbor Shari Skaggs said. “They told us we could get a free trip to Wal-Mart. No thank you. Definitely not worth that.”

The refusals would inconvenience future drillers, but the land men had already secured a deal with the mineral owners who mattered most: Steve and Vanessa White.